In A Garden Green

Creation Story Two: 2:4b-25

The Lord God planted a garden in Eden… and there he put the man he had fashioned… to cultivate and take care of it. 2:8,15

Introduction: let’s get leafy

Creation Story One, as we’ve seen, paints a big ole canvas that seeks to portray the palace domains of the King of the Cosmos. Sure, there’s fish in the sea and birds in the air and animals on the earth and greenery and fruit aplenty but they’re not really the focus - God is, along with His astonishing relationship with us humans. The setting, if you will, is out of this world spectacular.

The context for Creation Two is somewhat simpler at first glance. It’s a garden. The word ‘Eden’ in Classical Hebrew connotes ‘delight’ or ‘pleasure’. The Greek translation of garden gives us ‘paradise’ which means a royal park or enclosure but later acquires heavenly hues. And this is the point: garden = truly home. The settled intimacy of this walled space is sacred and nourishing. It gives shape to the human longing for an effortless unified experience of natural and supernatural. This theme is close to the hearts of many other Christian Substack writers Paul Kingsnorth The Wildroot Parables 🌿 Scoot and, of course, is deeply embedded in Christian consciousness thanks to, amongst others, St Francis of Assisi.

It’s worth pausing here, taking a seat in the mellow heat, to appreciate the garden’s beauty - the endless greens, the tall nobility of its trees, their delicious sun-kissed fruits. You know, before it’s all coloured by what’s to come. The writers are drawing readers’ attention to a preternatural simplicity: the restorative powers of the sacred grove. In other words, the choice of garden isn’t mere story setting. And deep wisdom here abides, even if you’re not a baldy, blue-faced, tree-hugging Celt like me.

Mythic Context

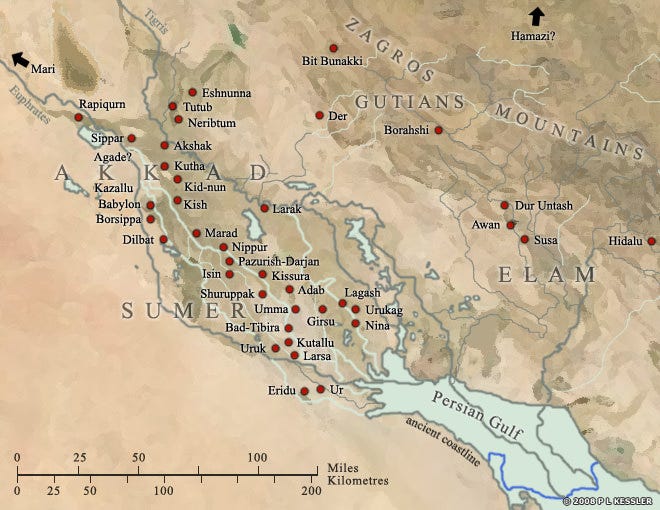

A swift eye over verses 10-14 reveals Eden’s ‘easterly’ location as modern day Iraq. This mythic setting relates to Ancient Mesopotamia in the Fertile Crescent - sometimes referred to as the Cradle of Civilisation, largely because it offers archeological evidence of some of the earliest known human settlements and culture. Why is this important? Well, numerous Mesopotamian myths have left indelible marks on the Genesis stories and understanding precisely how helps us discern what our inspired writers retained and what they rejected. Whatever is retained reflects God’s wisdom at work beyond Hebraic culture (revealing potential archetypes), and whatever’s rejected crystallises the peculiar contradistinctive character of the Judeo-Christian tradition.

Broadly, here’s what’s retained: a primordial man/king and wife representing innocent humanity are placed in a perfect garden to tend and guard the sacred fruit of a very special life-giving tree.

To varying degrees, elements of this template are echoed throughout other world mythologies. For example:

Greek: the garden of the Hesperides complete with orchard of golden, immortality-bestowing apples, the idealised pastures of Arcadia, and heavenly fields of Elysium and the Blessed Isles.

Norse: the holy ash tree Yggdrasil with roots and branches connecting earth and heaven and with wells of wisdom and fate at its base feeding the rivers of the world.

Chinese: Fanghu, Isle of Immortals, where lies the elixir of youth, covered with magical plants and trees retains its imaginative influence on Taoist garden design.

And, of course, most directly, Babylon extends the earlier Mesopotamian idealised garden obsession with wondrous ones that even hang.

[Interestingly, as per Gilgamesh, Egyptian creation myths resonate far more with Creation Story One and the Flood narrative (CC 6-8). More on this later.]

So, we have a verdant garden and this paradise is specifically created by God for humanity that they might attain immortality. And this setting is retained because it embodies the birth of culture, civilisation, faith and storytelling itself. The root meaning of the word ‘Eden’ is ‘plain’ or ‘steppe’ and points to a fertile river valley in arid lands where humans first settled, became less nomadic due to the abundance and dependability of resources, and began to record their own stories - about their origins, their histories and their gods. Our ability to be appropriately connected to our own identity, faith and wellbeing is commensurate with still-time taken in that sacred garden. This is literal as much as figurative. Have a look at how Karen atLife in the Real World captures and is captured by this correspondence through her camera lens.

Tellingly, though, here’s what’s rejected:

There is absolutely no theogony in the cosmogony. Sorry, just couldn’t resist that sentence. Multiple vying gods are not created, destroyed or resurrected in the making of the universe. There’s no cosmic battle between goodie and baddie gods

The universe is not made out of bits and pieces of gods, or has anything inherently evil in it

Humans are not dispensable playthings of the gods but a special creation with a marked destiny

The universe isn’t divine. We don’t worship it. Nature isn’t our mother or father.

[For the (other) mythology geeks in the house, the original source of Creation Two appears to be the Sumerian Enmerkar epics and the Akkadian Atra-Hasis which influence the later Gilgamesh]

This part of the world ☝🏻

So, there is but one benevolent creator God and the garden world He made for us is sacred. Given all the other mythologies, that’s a truly incredible statement. God cares! Every leaf proclaims it. What an immeasurable difference this makes to human dignity, purpose and awareness.

Rootedness

Gardens and trees and fruit emerge, then, as more than mere ornamentation or source material for story setting. It’s possible here to detect a profound psychological correspondence rooted in evolutionary biology. Dr Jordan Peterson excavates this with aplomb in his Genesis Lectures which I’ll discuss further on in the context of chapter three.

Before wrapping up our journey through chapter two, though, I’d like to take a literary turn and circle back to this idea of garden as home. Scripture has indelibly marked out the garden as having literal and mythic significance. Obviously, a story can be literally set in a garden - I’m just going to say Igglepiggle, (if you know, you know) - but, it’s actually more about the vestiges of Edenic vision: a way of seeing or writing. And it has something to do with the spirituality of place, the sacred rootedness of locality, the particular holiness of here.William Collen has been illuminating this theme for a while now.

As a Christian story writer, I often sense its presence pre-consciously. Here’s the rightly lauded opening paragraphs to the great Hem’s, A Farewell To Arms:

In the late summer of that year we lived in a house in a village that looked across the river and the plain to the mountains. In the bed of the river there were pebbles and boulders, dry and white in the sun, and the water was clear and swiftly moving and blue in the channels. Troops went by the house and down the road and the dust they raised powdered the leaves of the trees. The trunks of the trees too were dusty and the leaves fell early that year and we saw the troops marching along the road and the dust rising and leaves, stirred by the breeze, falling and the soldiers marching and afterward the road bare and white except for the leaves.

The plain was rich with crops; there were many orchards of fruit trees and beyond the plain the mountains were brown and bare. There was fighting in the mountains and at night we could see the flashes from the artillery. In the dark it was like summer lightning, but the nights were cool and there was not the feeling of a storm coming.

I don’t want to over-analyse it but, suffice to say, it’s this here-ness that only a story crafted from authentic vision can muster. And here, perfect words portray a broken garden. Yes, the fall always comes too soon!

The other master that springs to mind is Steinbeck. Obviously, he had the Bible in his blood with titles like East of Eden and The Grapes of Wrath but actually it’s the opening two paragraphs (again) of Of Mice and Men that supremely carry our sense:

A few miles south of Soledad, the Salinas River drops in close to the hillside bank and runs deep and green. The water is warm too, for it has slipped twinkling over the yellow sands in the sunlight before reaching the narrow pool. On one side of the river the golden foothill slopes curve up to the strong and rocky Gabilan Mountains, but on the valley side the water is lined with trees— willows fresh and green with every spring, carrying in their lower leaf junctures the debris of the winter’s flooding; and sycamores with mottled, white, recumbent limbs and branches that arch over the pool. On the sandy bank under the trees the leaves lie deep and so crisp that a lizard makes a great skittering if he runs among them. Rabbits come out of the brush to sit on the sand in the evening, and the damp flats are covered with the night tracks of ’coons, and with the spreadpads of dogs from the ranches, and with the split-wedge tracks of deer that come to drink in the dark.

There is a path through the willows and among the sycamores, a path beaten hard by boys coming down from the ranches to swim in the deep pool, and beaten hard by tramps who come wearily down from the highway in the evening to jungle-up near water. In front of the low horizontal limb of a giant sycamore there is an ash pile made by many fires; the limb is worn smooth by men who have sat on it.

Another perfect portrait of our Edenic hankerings worn down, beaten smooth and ultimately reduced to ashes even amid all that revelatory natural beauty.

I don’t normally talk about my own fiction but it is relevant here. One of the themes we’ll explore later is the mythic city as representative of lost Eden - Sodom and Gomorrah, Gotham or Sin City, if you will. But it’s more complex than this because God eventually ratifies a city and even comes to live in it. In my novella, The Pelican Crossing, London’s animus forms part of the sense of oppression bearing down upon the relationship of two teenagers. This is a deliberate channelling of the Genesis motif of city as lost Eden. However, it was equally important to find expression for the reverse motif of city as promise of recovery and so the key revelations occur in a city park garden. Their very lives are infused with this dual urban character of despair and hope. Fellow Christian writer, Danny Anderson, who was kind enough to review the story, identified this atmosphere with his usual perceptive precision: ‘…a city built as much from language as architecture.’

Conclusion: that vital double vision

Creation Story Two. Done. Let’s swing back to why there are two complementary stories. Poet Sally Read memorably used a phrase to capture our sense of God - far nearness - and this beautifully encapsulates the transcendence of Creation One and immanence of Creation Two. If we ever find ourselves slipping into over-familiarity with God, tempted to fashion Him out of our own preconceptions, or overstate our own importance, there’s Creation One. Equally, when overwhelmed, or feeling lost in the cosmos, we’re shown that a simple retreat to the shimmering fields, a walk in the wild woods, or a plonk down in the backyard with a numinous story might help us rediscover His deep abiding presence. Because, of course, it’s actually all one story.

If you know of other great fiction that equally captures this quality, comment me in. Or if you know of any other Substackers tackling these themes, please point me their ways. Many thanks.

Header Photo: Rehan Shaik, Unsplash

Wonderful thoughts here Adrian. You have me thinking much more intentionally about the labyrinth herb garden I'm designing in my own back yard. After reading this, I want to be much more thoughtful about the plants I put in there an how I might think more theologically about them. Thank you!